When I was a dumb young student, I spent most of my days skipping class, instead hanging out in the basement of the student union building, working as an editor at the campus newspaper. There, I happily spent the time writing articles, talking politics, and wading through the feverish swamp of what would now be called woke politics.

At the time, we all thought that skipping class and writing hard-left articles for a hard-left newspaper was a great way to fight the system. We thought of ourselves as the underdogs, the dropouts, the resistance. It was assumed at the time that it would be the business students, busy giving presentations and wearing suits and ties, who would one day take possession of the keys to the kingdom.

And yet, a strange thing happened with the passage of time. The young radicals I used to hang out with all grew up to be pretty successful. Some became journalists, others became doctors, professors, lawyers, politicians and entrepreneurs. We each discovered that following our passion, instead of undermining the system, quickly turned us into a system. Along the way, most of us also got rich, in some cases embarrassingly so.

In retrospect, it shouldn’t have been such a surprise. It turns out that the qualities of character and mind required to spend 40 hours a week doing unpaid volunteer work writing and producing a student newspaper, while still managing to complete a full load of college coursework, are qualities largely rewarded by the capitalist system. . What we imagined to be an act of resistance was actually just a flex.

I was reminded of this recently by the subtitle of Krzysztof Pelc’s new book, “Beyond Self-Interest: Why the Market Rewards Those Who Reject It.” Pelc is a professor of political science at McGill University, who in recent years has received awards for his writing of fiction and non-fiction. Perhaps encouraged by these successes, in this book Pelc goes far beyond his first love, which is international trade agreements, to reflect on deeper aspects of the modern condition.

Pelc is not the first to observe something paradoxical about the relationship between market success and people’s attitude toward that success. More than a century ago, Max Weber noted an apparent correlation between the Puritan attitudes of certain Protestant sects and their success in business ventures. This was partly due to their strictness and self-discipline, which led them to be exceptionally methodical in pursuing their goals. It was also their hostility to earthly pleasures that led to a dramatic increase in their savings rate, which in turn increased the amount of capital available for investment.

As Weber observed, the path to wealth involves not only earning lots of money, but also not spending it. Many people, and many societies throughout history, have succeeded in one or the other, but rarely in combination. The secret to success lies in finding a value system that encourages people to work hard but refrain from enjoying the fruits of that labor.

There is such a constellation of values in contemporary anti-consumerism, which is why so many supporters of this movement find themselves accused of “selling off”. Naomi Klein proved long ago that the market for anti-capitalist literature is both vast and hugely lucrative. But there is something more deeply paradoxical in the anti-consumerist position. Fighting back against the planned obsolescence of the modern consumer economy, whether by participating in the annual Buy Nothing Day or supporting the Right to Repair movement, are all different ways to cut your spending. And yet, if you reduce your expenses without also reducing your income, you end up saving, which in the long run just gives you more to spend.

Like many people my age, I was raised by parents who drank heavily from the anti-capitalist well of the 1960s. I grew up believing in self-reliance, whether it was building my own patio, to clean my own house or take care of my own children. Housekeepers and nannies were too much like servants to be comfortable. Paying rent to a landlord seemed like a complete waste of money. And perhaps most importantly, I had a visceral horror of debt, especially credit card debt. Over time, however, I was forced to recognize that the major consequence of these personal values was that they made me a wealthy older person.

Pelc takes note of these traditional paradoxes, but he thinks much more is happening in the modern economy. As our consumption of material goods approaches satiety, we find ourselves seeking other, more esoteric qualities. He is struck, for example, by the many stories of successful business lawyers or bankers who quit their jobs to pursue a passion for artisanal baking or making small batch sriracha.

Although these businesses are usually portrayed as the pursuit of passion rather than profit, it is hard to avoid noticing that the resulting businesses often succeed in highly competitive markets where many others have failed. According to Pelc, part of the reason for the success of these companies, despite their rejection of corporate values, is that they have an effective response to the challenge of creating trust in a market economy.

As consumers become less interested in the material qualities of goods and more interested in their spiritual and social qualities, we also come to rely more on representations made by sellers. The dimensions of a rug can easily be assessed, while the claim that it was made by hand on a traditional loom is more difficult to verify. Many people are willing to pay more for the homemade version, but only if they believe it’s genuine. The obvious solution is to buy your rug not from the usual factory outlet, but from some crazed luddite who shears his own sheep and rejects all modern technology.

Therein lies the beauty of true believers. Precisely because they are not in it for the money, the claims they make about the qualities of their products are much more believable. The problem with traditional economic interest is that it leads to opportunism, which undermines trust. As the economy becomes more and more dematerialized, trust becomes more important to every transaction, and so people who are too obviously in it for the money find themselves at a competitive disadvantage.

A similar phenomenon can be found on the workers’ side. In a rather stark rejection of Don Draper’s theory of workplace validation (“that’s what the money is for!”), young people in particular seek deeper forms of job satisfaction, including including the belief that they are at the forefront of the struggle for social justice. This has led to some strange corporate behavior, including Unilever’s widely mocked decision to announce that Hellman’s mayonnaise’s primary purpose was no longer to add flavor to sandwiches, but to lead the fight against food waste by encouraging the consumption of leftovers. Many have wondered if it was strictly necessary for mayonnaise to have a higher social purpose.

Yet it can hardly escape notice that employers who make a more credible effort to persuade their workers that they don’t care about money, but rather act for a higher purpose, will be able to obtain much higher levels of commitment and work effort. This will in turn help them earn a lot more money. As work becomes more abstract and difficult to oversee, this ability to elicit real worker engagement becomes a crucial competitive advantage.

As a result, bad-talking corporate profit has become an increasingly effective strategy for maximizing corporate profits.

There are many goals in life that resist our efforts to achieve them directly. This is the case with social status, where wanting it too much, or appearing to want it, can interfere with its acquisition. Relaxation has a similar quality. Although we constantly tell others to relax, it is difficult to obey the instruction because forcing ourselves to relax can be very stressful.

Some philosophers have described what they call a “paradox of intention” in these areas. Some desirable states can only be achieved as a by-product of activity directed toward another goal. Adopting them as an explicit goal is counterproductive.

This paradox underlies another general trend that Pelc diagnoses, which he describes as the emergence of a “byproduct society.” Because modern industrial civilization has become so efficient at achieving ordinary goals, such as food, shelter, and clothing, which respond directly to forceful intervention, we have set in motion a dynamic that has increased the relative importance side effects. We care less about material goods and more about experiences, but because of this, our direct interventions to maximize productivity become less effective over time.

This transformation affects us not only as consumers but also as workers. Companies increasingly want their employees to be creative and innovative, something that cannot be achieved through forceful intervention. And so they end up encouraging them to work less, or focus on “mindfulness,” in the hopes that it will make them better workers.

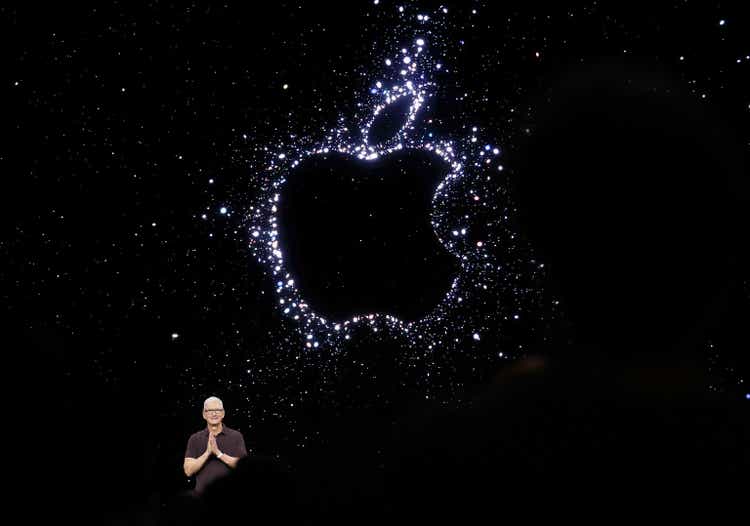

Because of these trends, those who succeed in the modern economy are often those who avoid doing too much. The best example of this is the modern tech business, where the founders just built something cool, with monetization after the fact.

But of course, one cannot dismiss the market too much and still hope for success. I once met a carver whose way of maintaining his artistic integrity was to focus on creating small piles of hollow rock in unmarked spots on the shores of lakes in northern Manitoba. Chances are you’ve never heard of him, because his strategy to avoid selling out was a bit too effective.

Pelc’s paradigm is an artist like Banksy, who seems downright serious in his disdain for the wealthy collectors who buy his art, and yet responds quite assiduously to the market’s demand for attention-grabbing stunts. This is a kind of mental gymnastics, which allows some individuals to achieve a happy balance between being a fanatic and an impostor.

What the market rewards in these cases is a certain capacity for self-deception, the ability to believe that you are fighting the system while simultaneously reaping its rewards. If Pelc is right, this particular form of hypocrisy has ingrained itself in every aspect of modern life; it’s no longer just for annoying college students, who complain about locked doors while snatching keys.

:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/opinion/contributors/2022/07/02/down-with-capitalism-for-people-and-companies-alike-theres-a-new-path-to-profits-follow-your-dream-and-trash-talk-profits/banksy_illo_web.jpg)